Continuing on from my last article about shooting in sub-par lighting, I’ll introduce my next roll of film—RPX 400 from Rollei. I usually like this film. This roll also marked the first time I really tried to use the Tone Curve tool in Lightroom. I’m still getting used to it. But I thought that with RPX 400, I might be able to make some ordinary prints somewhat less ordinary.

After forty years of doing this, you’d think I’d have it all figured out. You’d think I’d have a fixed workflow, a set of rules, a way of knowing exactly what the result will be. But this roll reminded me otherwise. There’s always something new to learn, or something old to look at differently. And I’ve started to wonder if there’s something honest in admitting that, rather than pretending the process is ever truly finished.

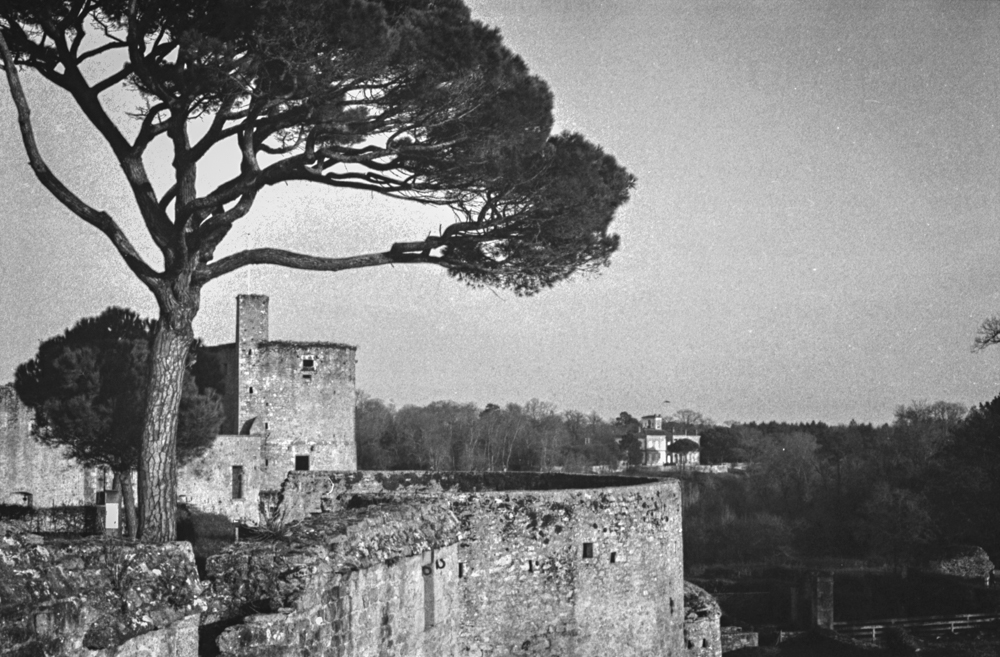

Pont Caffino on a February afternoon is exactly that kind of place. I’d never visited before, though I’d heard about it from other photographers. The sky was uniform. The light was flat. Nothing was going to jump out and grab me. So I loaded the Rollei, walked down to the river, and started looking.

The River

The water level was low—noticeably so. I knew this because not long before, I’d been at the Maine in St Hilaire de Loulay where the river had broken its banks completely. You couldn’t even see the weir there, just water spreading across the landscape. Here at Pont Caffino, the opposite was true. More of the granite banks showed through. More of the weir structure was exposed. The river looked different, and I found myself photographing it differently.

When the light is flat, water becomes less about reflection and more about texture. You notice the foam patterns, the subtle ripples, the way debris catches on submerged rocks. RPX 400 handled this beautifully—there’s a softness to the water that feels accurate to how it looked that day, not how I wished it looked.

The gauges became an unexpected focal point. They’re functional objects, not particularly beautiful on their own, but they tell the story of this place better than any dramatic landscape could. The reflection of the numbers in the still water added a compositional echo I didn’t plan but gladly kept.

Where the water quickened over the weir, I had to be careful with exposure. Film handles highlights more forgivingly than digital, but I still metered conservatively. The fallen branch caught my eye—it’s the kind of detail you miss when you’re looking for the big shot, but it adds a diagonal line that pulls the frame together.

On editing the water: The challenge here was separation. When both sky and water are grey, they tend to merge into one another. I used subtle dodging to lift the highlights on the water’s surface, just enough to ensure the reflections didn’t disappear. Nothing dramatic. Just enough to guide the eye.

The Cliff Face

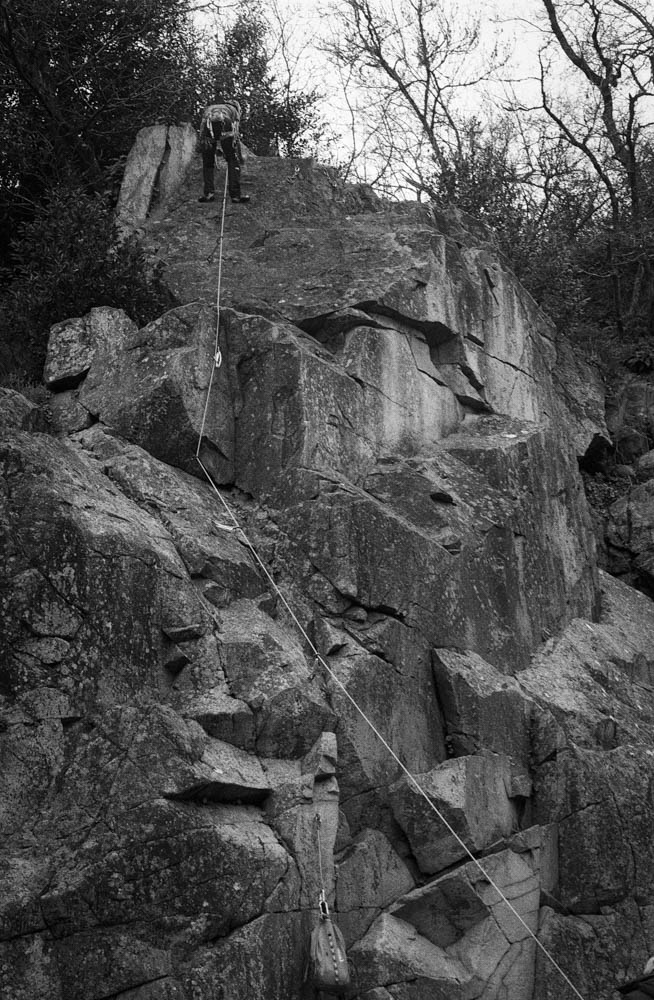

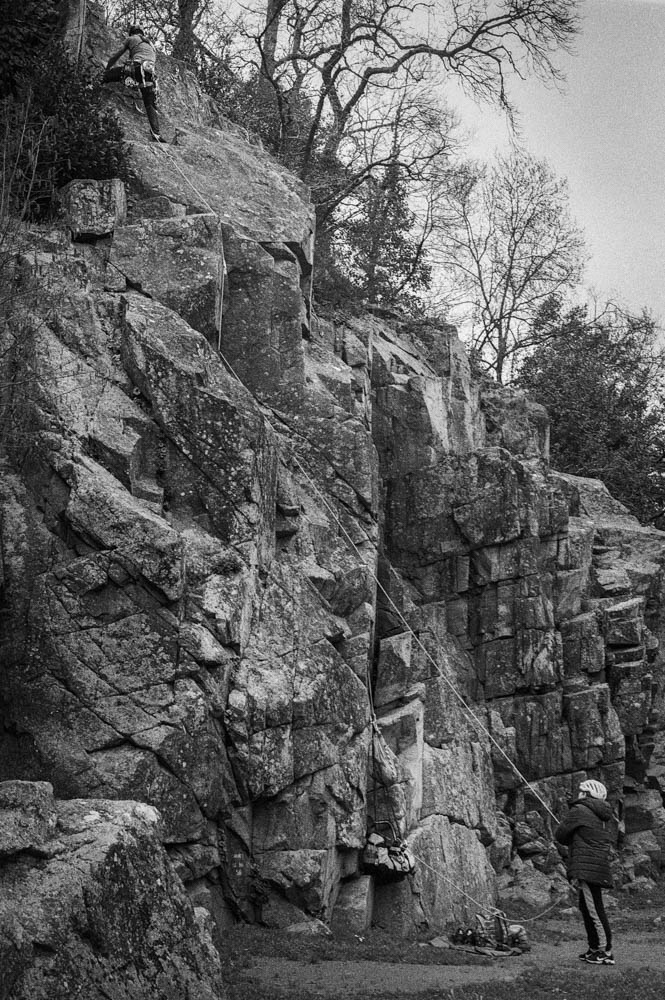

The granite cliffs that frame the Maine valley are dramatic even in bad light. They’re also popular with climbers, which adds a human element I hadn’t planned to capture but couldn’t ignore.

I haven’t shot rock faces like these on HP5+ before. The nearest I got to that was shooting in the Pyrenees mountains—different stone, different light, different everything. So I didn’t have a direct comparison to fall back on. What I noticed with RPX 400 is how it renders texture without aggression. Every crack and lichen patch comes through, but without the bite that HP5+ might have given. For this particular day, that suited the mood better.

Seeing the climber and belayer together reminded me that landscapes aren’t empty. They’re used. They’re lived in. The rope creates a diagonal line through the frame, and suddenly there’s narrative—someone is trusting someone else, and both are trusting the rock.

On editing the cliffs: This is where dodging and burning did the most work. Flat light makes rock faces look two-dimensional, like cardboard cutouts. I spent time burning in the crevices and dodging the raised surfaces, essentially repainting the light that wasn’t there when I pressed the shutter. It’s not about creating drama that didn’t exist. It’s about revealing the dimension that the light flattened.

Details

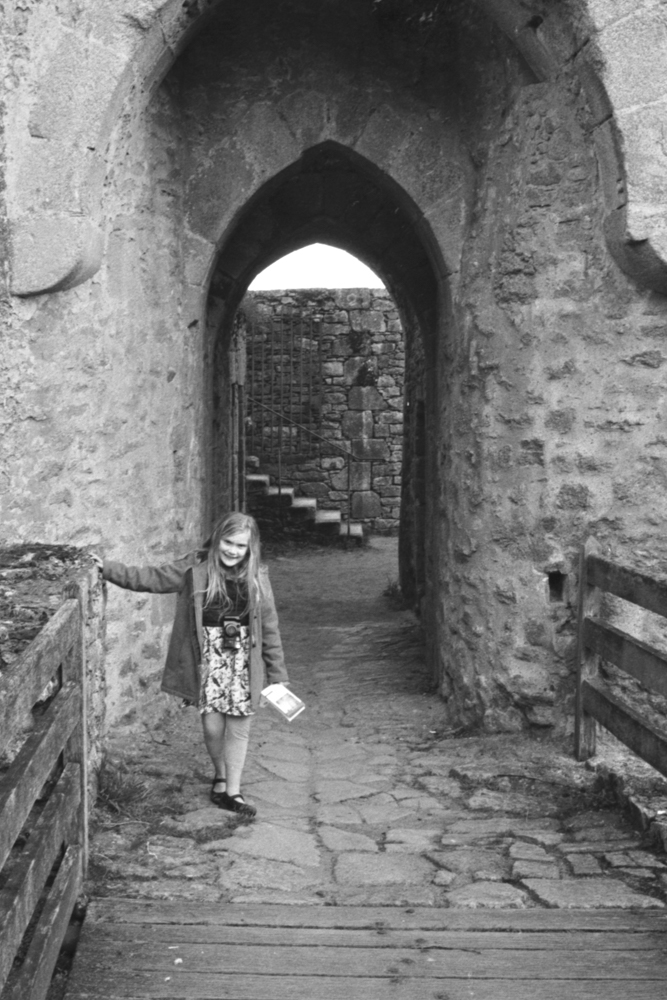

I’ve learned to slow down on days like this. When the big vistas aren’t cooperating, the small things start to speak.

The catkins hanging from bare branches aren’t dramatic. They’re not even particularly interesting as a subject. But they caught the light in a way that felt worth capturing. The shallow depth of field creates a dreamy quality, and the grain—more noticeable here than in the landscapes—adds character rather than detracting from it.

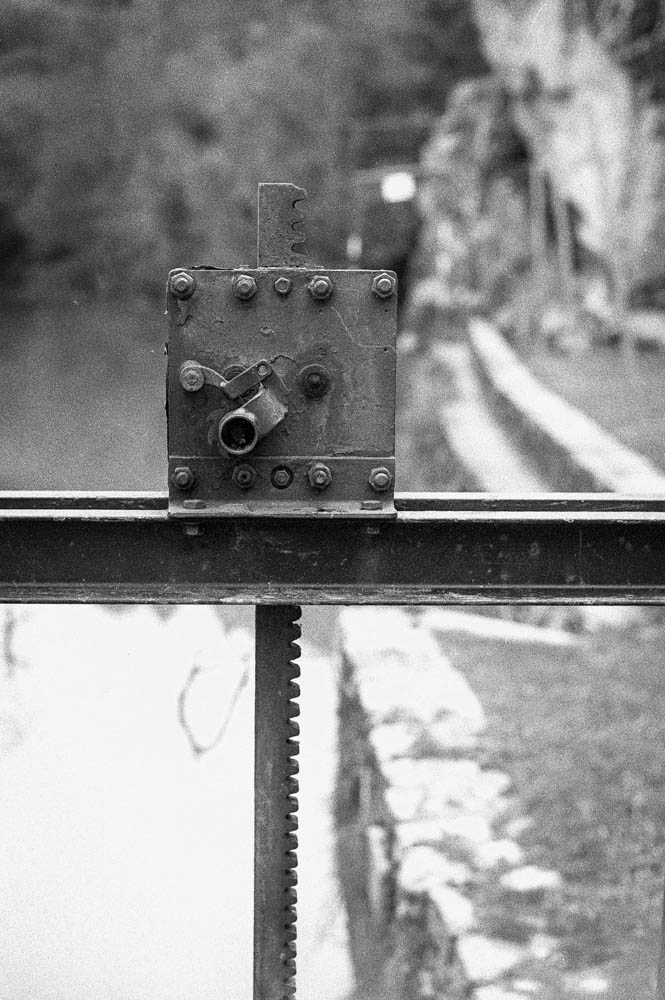

The mechanical detail—the lock gate mechanism, I think—was almost accidental. I was walking back from the viewpoint and noticed the bolts, the geared rack, the weathered metal. It’s the industrial counterpoint to all the natural elements. Sometimes you just stop and shoot because something looks like it has a story.

On editing the details: I was careful not to over-sharpen these. The natural grain of RPX 400 provided enough texture without needing digital enhancement. If anything, I pulled back on clarity rather than adding it. These images work because they’re soft, not in spite of it.

The Town & Viewing Platform

For the full perspective, I drove up to Château-Thébaud’s belvedere, “Le Porte-Vue.” It’s a striking piece of architecture—Corten steel extending 23 meters out at 45 meters above the river, designed by Emmanuel Ritz and inaugurated in 2020.

Walking out onto the platform, you feel the height. The steel underfoot, the railing at your side, the valley opening up below. There’s a figure in this shot—could be another photographer, could be anyone taking in the view. It adds scale and reminds you that you’re not alone in these places.

The Corten steel handled the flat light better than I expected. The weathered texture gave the film something to hold onto, and the geometric lines contrast nicely with the organic landscape beyond. The framed view through the steel structure became one of my favourite shots—it acknowledges that you’re looking from somewhere, not just capturing a scene.

This is the establishing shot. The full Maine valley from above, all the elements visible at once. You can see the weir, the cliffs, the tree line. After seeing the Maine at St Hilaire de Loulay with water everywhere, this view felt almost spare. The lower levels exposed more of the structure than I’d imagined possible. It’s the image that ties everything together.

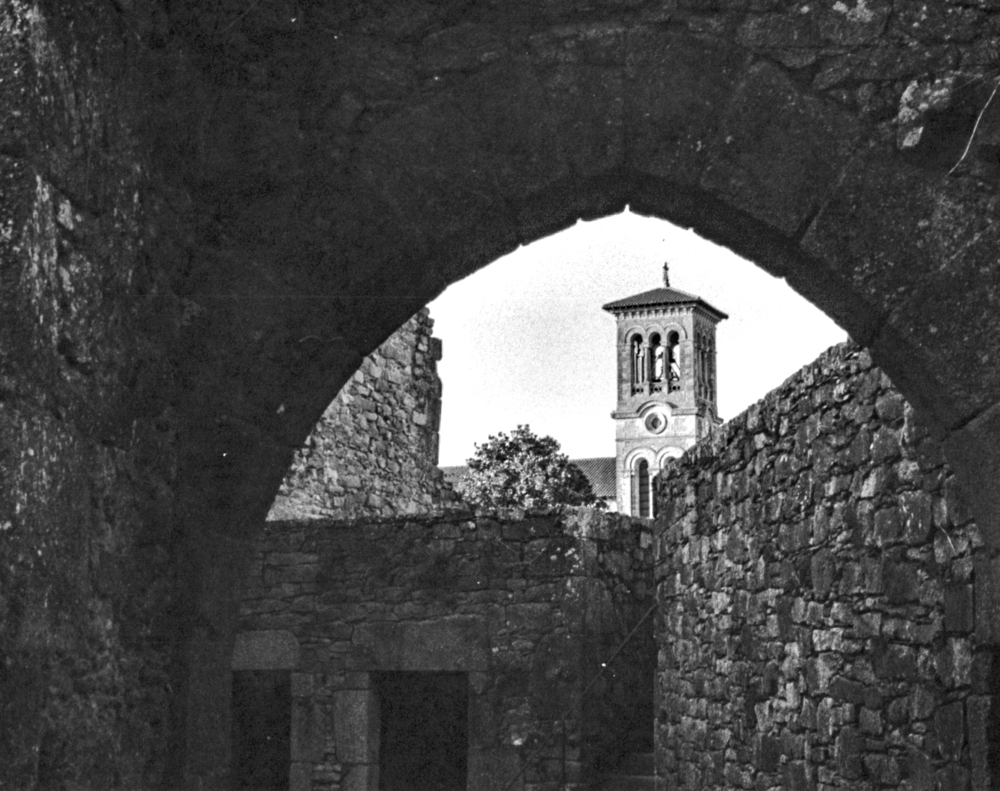

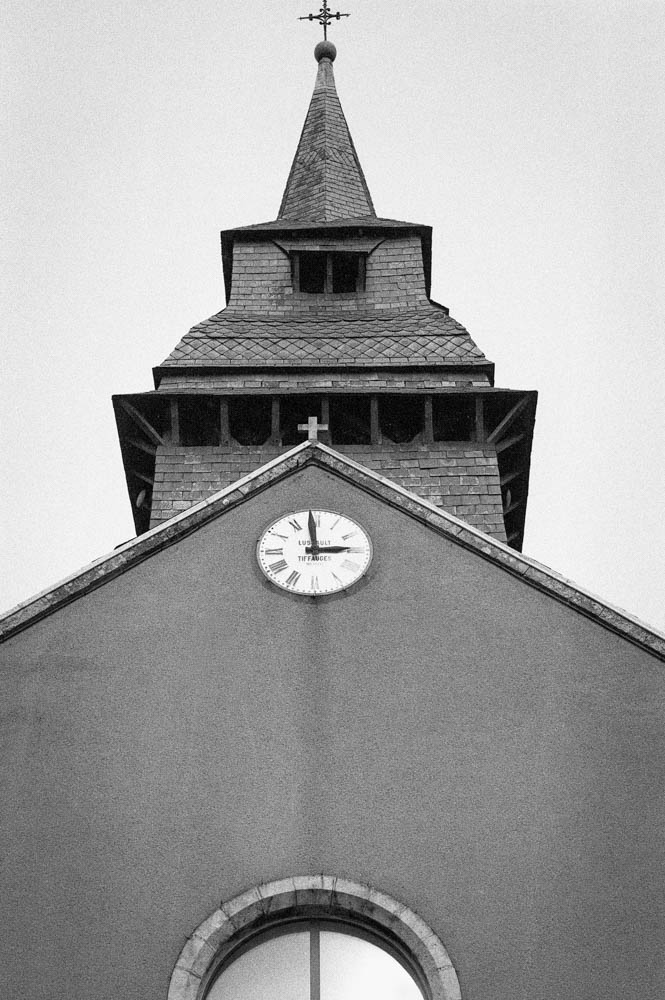

The village itself grounds the landscape. The church steeple adds a human landmark to the valley. The quiet street with its leading lines and the number “28” on the wall—these are accidental details that add authenticity. This isn’t a pristine wilderness. It’s a place where people live.

On editing the architecture: I focused on straightening lines and ensuring the steel texture didn’t look too smooth. The flat sky was retained intentionally. I could have blown it out or added artificial clouds, but that would have been dishonest. This is the light I had. This is the day I experienced.

On Making It Less Ordinary

Looking down at the river from Le Porte-Vue, I thought about what I was actually trying to do.

This was my first time at Pont Caffino, and I wasn’t sure what to expect. RPX 400 felt right for this quieter, more exposed version of the valley. But the film alone wasn’t enough. The scans came back flat—accurate, but lacking the dimension I remembered from being there. That’s where the work began.

In Lightroom, I used the Tone Curve to add a gentle S-shape, nothing aggressive. Just enough to add punch without crushing the blacks. I lifted the deepest shadows slightly to preserve the atmosphere. And then I spent time dodging and burning—manually painting light into the highlights of wet granite, holding back exposure in the shadows of riverbanks, guiding the viewer’s eye through texture and tone.

I’ve only started using the Tone Curve with this roll of film. I’m still getting used to it. But I’ve found it offers basic yet subtle controls, as does the dodging and burning. It’s easy to feel like this is cheating. Like you’re admitting the photograph wasn’t good enough straight from the scan. But I’ve started to think of it differently. Dodging and burning isn’t about fixing mistakes. It’s about translation. It’s about taking what you saw and felt and finding a way to communicate that to someone who wasn’t there.

There’s a danger in thinking you know everything. Usually, that’s when you stop seeing. When you assume the light will behave, or the film will respond the way it did last time, you miss what’s actually in front of you. I’d rather be the one still figuring out the Tone Curve after forty years than the one who thinks there’s nothing left to learn.

The result isn’t dramatic. It’s not the kind of image that stops you scrolling. But it felt honest—a quiet enhancement rather than a transformation. And on a grey February day at Pont Caffino, that’s exactly what I was after.

Technical Note

| Film | Rollei RPX 400 |

| ISO | Shot at 400 |

| Camera | Nikon FE |

| Lens | 50mm f/1.8 Nikkor |

| Development | Ilfosil 3 (1:9) |

| Scanning | Plustek OpticFilm 8100 |

Lightroom Adjustments:

- Tone Curve: Gentle S-curve, highlights lifted slightly, shadows preserved (First serious use of this tool for me)

- Local Adjustments: Radial filters for dodging/burning on rock textures and water surfaces

- Grain: No reduction applied

- Sharpening: Minimal, applied selectively on details

Thanks for reading. If you’ve shot RPX 400 in similar conditions, I’d love to hear how you approached it.