Capturing Fleeting Moments

When we talk about a moment in time, that moment is no longer the present; it has become the past. We cannot repeat it, nor can we reclaim it. It has happened and will never come back. Photography is an art form that allows us to capture a specific moment and preserve it for all time. We know that it is impossible to capture exactly the same conditions in which the shot was taken. We can attempt a recreation, but it will never be identical. Time has moved on to the next moment.

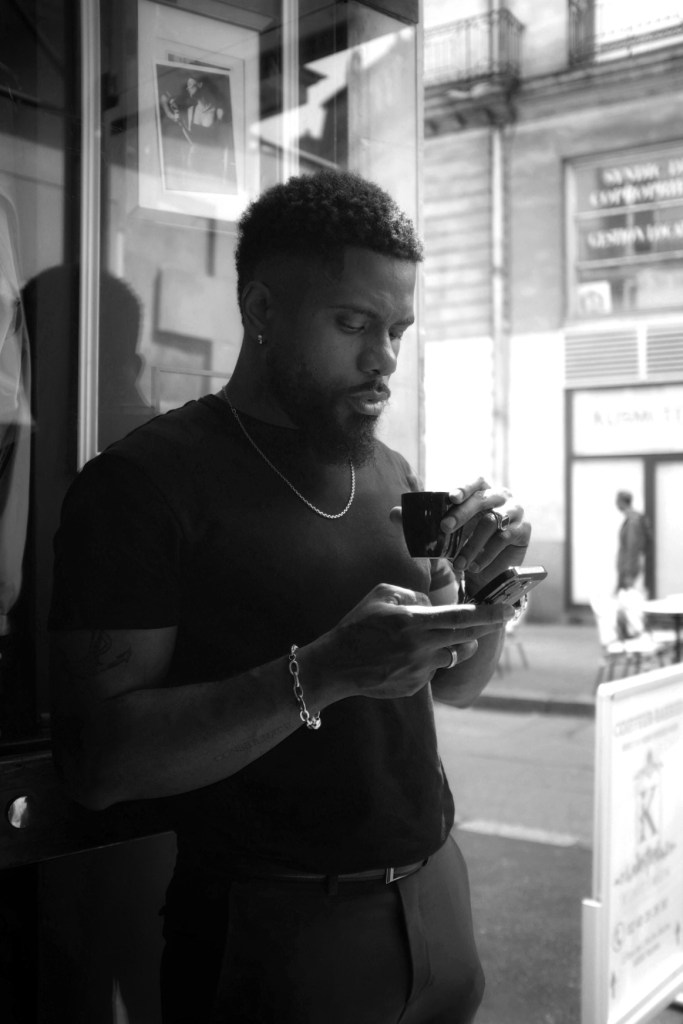

As photographers, we are left with the task of capturing the present, knowing it is already slipping away. What does this mean for the way we approach our art? Will we constantly look back, regretting the passage of time, or will we, on the contrary, feel privileged to have documented it for the future?

This brings us back to the idea of preserving the decisive moment that Cartier-Bresson spoke of. Like comedy, it would appear that photography is all about timing.

When we capture that moment, we must decide how we want to portray it. Do we want to freeze the action with a very high shutter speed, or can we slow down and add a sense of movement to our image? How fleeting is the image we are trying to capture? What will this motion add to the image?

My approach

Over time, I’ve come to appreciate these fleeting moments in time and try to document them, whether in the big city or out in the countryside with my children—especially when they play together. I want the spontaneity of it all, to capture those precious moments of complicity. As any parent knows, our children grow up before our eyes, and before we can truly realise it, they are grown up. Even when they’re not together, and I look through these past moments in time, I get an overwhelming feeling of, “Where did it all go?” My son is 25, and my daughter is 15 already.

Embracing Mistakes: A Journey to the Image

I’ll admit, I’m not one to embrace mistakes easily. I’ve always strived for precision in my photography, seeking to control every variable and meticulously plan each shot. I don’t like leaving things to chance, and so, when things don’t go as expected, there’s often a twinge of frustration. A blurred shot, an overexposed image, or a missed moment—those mistakes are a part of the process I try my hardest to avoid.

But over time, I’ve started to realise something: these mistakes, as unsettling as they may feel in the moment, are often a necessary part of the journey toward the image I’m truly after. When I reflect on the photographs I’ve captured, it’s clear that the path to the perfect shot wasn’t a straight line. It was made up of trial and error, of learning how to see the scene in front of me not just through my lens, but also through the lens of my mistakes.

It’s the misfires, the accidents, that force me to reconsider my approach, to adjust my frame or my focus. They open my eyes to perspectives I might not have considered, angles I might not have thought of, and emotions I might not have expected to capture. Each mistake teaches me something new, something that nudges me closer to that elusive, perfect image. They’re not setbacks, but rather signposts that guide me, sometimes uncomfortably, to a place where I can see the photograph with fresh eyes.

I’ve come to understand that each imperfection is part of the journey. The photograph I end up with is rarely the first shot I took, or the second, or the third. It’s the culmination of countless adjustments, failures, and moments of doubt, all leading me to the image that feels right. In the end, I realise that without those mistakes, the image I’m truly after might never have come into focus.

So while I still seek control, I’ve learned that there is value in embracing the unexpected. It’s in the mistakes, the missed moments, and the misjudgments that I find the essence of my photography. They are just as much a part of the creative process as the moments of perfection, guiding me closer to the image that speaks to me—and perhaps even to the viewer—most clearly.

Conclusion: The Beauty of the Journey

Photography, at its core, is a celebration of the fleeting moments that pass us by in the blink of an eye. The act of capturing these moments is an acknowledgement that time is forever slipping away, and in that impermanence, there is both beauty and significance. As photographers, we are tasked with documenting not just what we see, but also what we feel—the raw, unrepeatable essence of time itself.

The pursuit of the perfect image is a delicate dance between intention and spontaneity, control and surrender. It’s a journey that, more often than not, veers off the well-trodden path and into uncharted territory. Along the way, mistakes become our teachers, guiding us toward discoveries we might never have made if we had stayed within the confines of our comfort zone. These missteps, rather than being failures, are integral to the creative process, pushing us to reimagine, reframe, and reinvent our approach.

In the end, photography is about embracing the imperfection of both the world around us and our own creative efforts. It’s in the mess, the mistakes, and the fleeting nature of the moment that we often find the most powerful images. And while the perfect shot may remain elusive, it is in the journey—the trial and error, the fleeting moments, and the lessons learned—that the true beauty of photography lies.

So, as we continue to document our world, let us not only cherish the decisive moments but also embrace the imperfections that make them meaningful. For it is through the transient, the imperfect, and the unexpected that we capture not just images but stories—stories that resonate with the heart and echo the passage of time.