How many times have I seen grown men go to pieces at the suggestion of using manual mode? Or worse, how many times have I seen other grown men saying that to be a real photographer you have to master manual mode otherwise you’re not a real photographer? Let me assure you that it’s not as complicated as it sounds. When I took my first photography lessons in 1984, I learnt it as a child. You’ve got this, and I’m here to accompany you through the process. As the Hitchkiker’s Guide so elegantly says, in comforting letters, “Don’t Panic!”

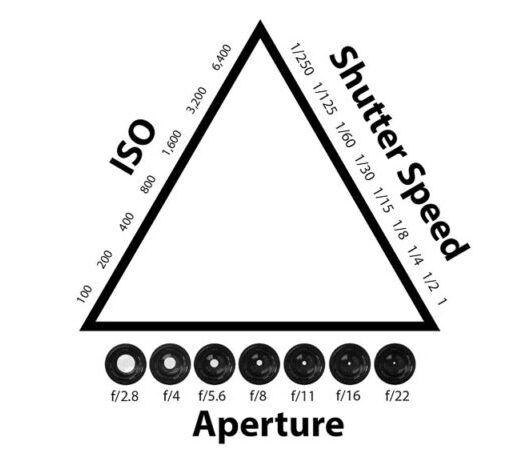

There are some basic concepts to understand, the first of which is the exposure triangle which we were introduced to in the Photography 101 article. Those three things to consider are, ISO, or film sensitivity, shutter speed, aperture, and balancing them together.

Are you ready? We’ll go step by step telling you how each of these settings influence your shot, and how we will balance them to create the image that “you” want instead of the image that your “camera” wants to take. You are the creative boss after all. And that is the reason that people use Manual Mode.

ISO, or film sensitivity

When I started learning photography in the last century was I was a young boy, yes I was young once, we only had film as a means to capture our images. You would choose your film in function of the light available. And when using my film cameras I still work in this way. 100 ASA (which is the same as ISO on modern camera) for sunny conditions, sometimes even 50 ASA, where the film can be used in bright conditions, going through to 200 ASA when it’s cloudy, but with sun shining through, to 400 ASA when overcast, 800 ASA when inside or even 1600 ASA, to 3200 ASA for night photography.

In the film days we would talk about the presence or absence of grain and this was part of the deal. You would get less grain the lower down the ASA range you went, and more grain the further up you went. And this grain was a result of the crystals on the film emulsion, and the chemical developing process. The choice could be as much about lighting conditions as an artistic decision. Once the film you chose was in the camera however, it didn’t change until you changed your film.

Nowadays with all this modern technology palaver, you can change this ISO (because it’s digital photography) and change it for each photo. Unfortunately the higher up you go in these values, the more “noise” you will get. This digital noise is in a random pattern and totally unlike the grain of film photography.

Shutter speed

Shutter speed, as the words suggest, is about the speed of which the shutter opens and closes to expose either the film or camera’s sensor. You see, I told you that this would be simple to understand. If I can get it, then so can you. So now we’re on to speed. When changing the speed of which the light hits the film or the shutter, I can freeze motion, of get a conscious motion blur, where the photo will seem animated.

Let’s say I want to take a photo of somebody running towards me. I will use a higher shutter speed to freeze the action. Think of sports photography, of catching a pass of a ball in rugby, or a footballer stopping a ball etc. Those factors will make or break your image. Imagine a photo of a football match and you can’t see the ball because it’s going faster than your shutter. It might not work out for you. In this situation, on my film cameras I will let the shutter curtain open for just 1/1000th of a second. Depending on which digital camera I can go as quick as 1/8000 th of a second.

Let’s go to the other extreme. I’m taking photos of a landscape and I want to show the motion of trees in the wind, the movement of the clouds, or the movement of water. I will use a longer shutter speed, say anything from 1/8th of a second to one second… The subject will be moving faster than the shutter curtain, and I will get that artistic blur.

I could be somewhere very dark, so in order to get a clear photo, I will have to let more light through onto my film or sensor.There I might have to use bulb mode in order to leave the shutter curtain for longer than 2 seconds.

For shooting a subject walking I would use 1/125th to 1/250th of a second to freeze the frame. When using a flash in manual mode, I would aim to be around 1/60th of a second (which depends on your camera’s flash sync value). When talking about shutter speeds I’m thinking of my film cameras and bearing in mind that most digital cameras will have wider ranges of shutter speed. Another tip for you would be to not let your shutter speed go below the number of your focal length (the legendary reciprocal rule). Let’s say I’m using a 50mm lens, then I would not use a speed under 1/50th of a second, or even 1/60th of a second. If I have a 200mm lens I would not go under 1/200th of a second. This is to counterbalance the weight of the lens and avoid lens shake.

Conclusion

This article has a lot of information in it and I have decided to separate everything and have a Part II. In this Part I we have talked about sensitivity to light be that film, and the different ratings of films for various lighting situations. In digital photography we have a wider range of ISO settings and with the newer cameras, the noise in an ISO 3200 setting will produce a much less grainy image than with film. However this “grain” can be used as an artistic choice and I will let “you” experiment and see what each film gives you.

We have talked about shutter speed, and the ability to freeze an instant with a higher speed. And the opposite of this to create motion in our image.

Next week we will talk about Aperture and how this effects depth of field and discover the rich creaminess of bokeh. We will also explore various scenarii and give concrete examples of the effects of this triangle and how to turn it into an advantage.