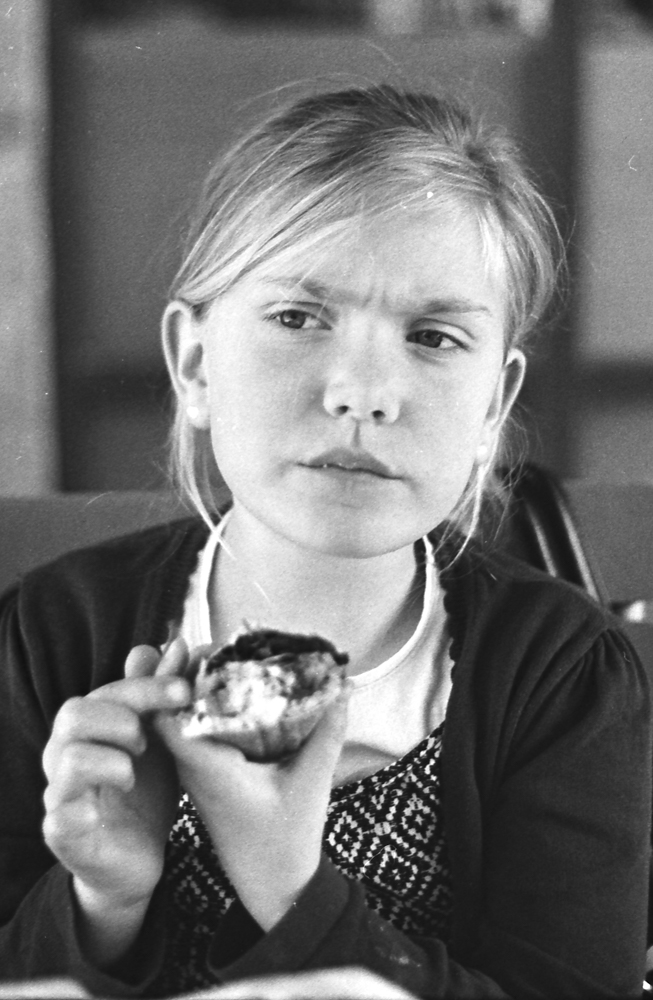

I often find myself discussing the concept of “vintage” with my father during our phone calls. I live in France, while my parents are in Northumberland. The term “vintage” means different things to different generations. For my 25-year-old son, vintage clothing is anything from the 90s—he even sports a few of my sweaters from that era. At 52, I’m beginning to see myself as slightly vintage, with a style that has evolved into something more classic and refined compared to my younger years. And to my 15-year-old daughter, my father, who grew up during the war, must seem positively ancient.

So, what does this have to do with photography? For me, a camera from the 1990s feels relatively modern, while those from the 80s and 70s seem older but not quite ancient—much like myself. Using these older cameras in my photography practice forces me to slow down and be more deliberate. Just as my style has become more refined with age, these cameras have an enduring elegance and charm. They may be from a slightly bygone era, but they still capture images with timeless grace.

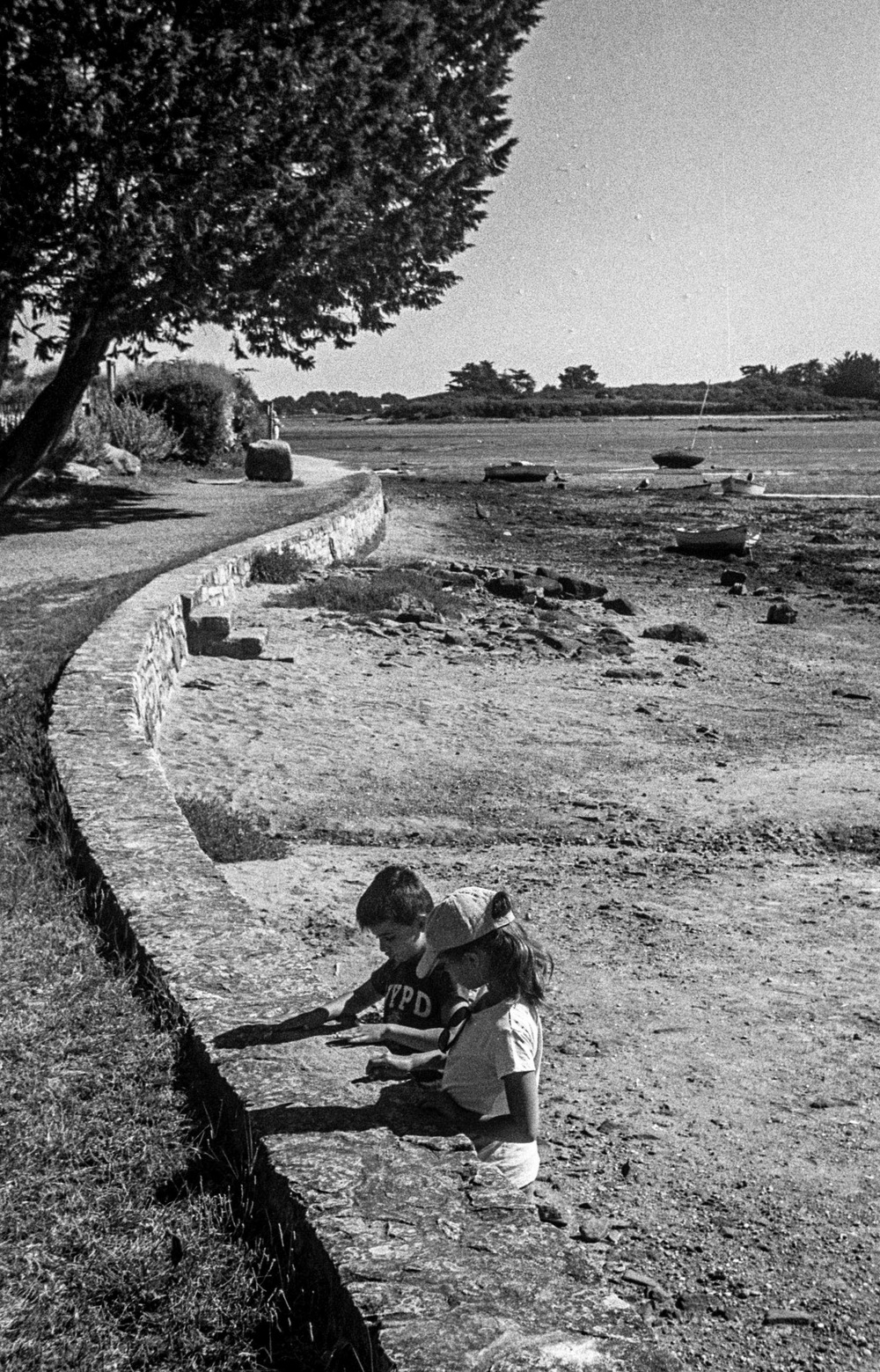

Incorporating this vintage technology into my work isn’t just about using old equipment, however enjoyable working with what could be considered museum pieces may be; it’s about embracing a process that demands patience and mindfulness—concepts that are somewhat foreign to this younger generation. Each shot taken with these cameras becomes a deliberate act, mirroring how I approach life and photography. The result? A deeper connection to the process and a greater appreciation for the unique quality of film. This slower pace allows me to savour each moment, akin to how my evolving style reflects a deeper appreciation for life’s subtleties.

In a world increasingly dominated by digital immediacy, there’s something profoundly satisfying about the slower, more thoughtful pace of using vintage cameras. They may not be the latest technology, but their classic design and the deliberate process they require make them a joy to use—much like the evolving sense of style and perspective that comes with age. The emotional impact of working with these cameras is profound; they carry the weight of history and personal connection, enriching my creative process and deepening my engagement with photography.

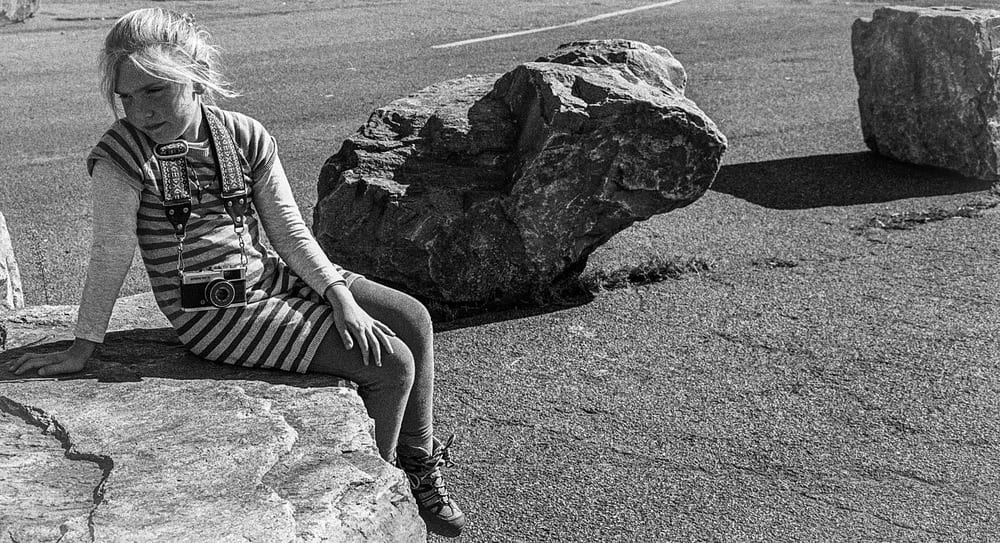

My own “vintage collection” began with an SLR from the 1980s: an East German Praktica MTL3 that served me faithfully until 2009. After it finally gave up, I quickly replaced it with another. From there, I delved into exploring more iconic cameras from the 1970s and 1980s. At that time, they were still relatively affordable before the hipsters discovered film photography and the prices inevitably started rising.

My exploration didn’t stop there. I began to seek out cameras from the 1960s and even the 1950s. The oldest camera in my collection dates back to 1949! It’s quite vintage, even for me, though perhaps not so much for my father. Each piece of my collection is a link to a past era, offering a tactile connection to history that digital tools can’t replicate.

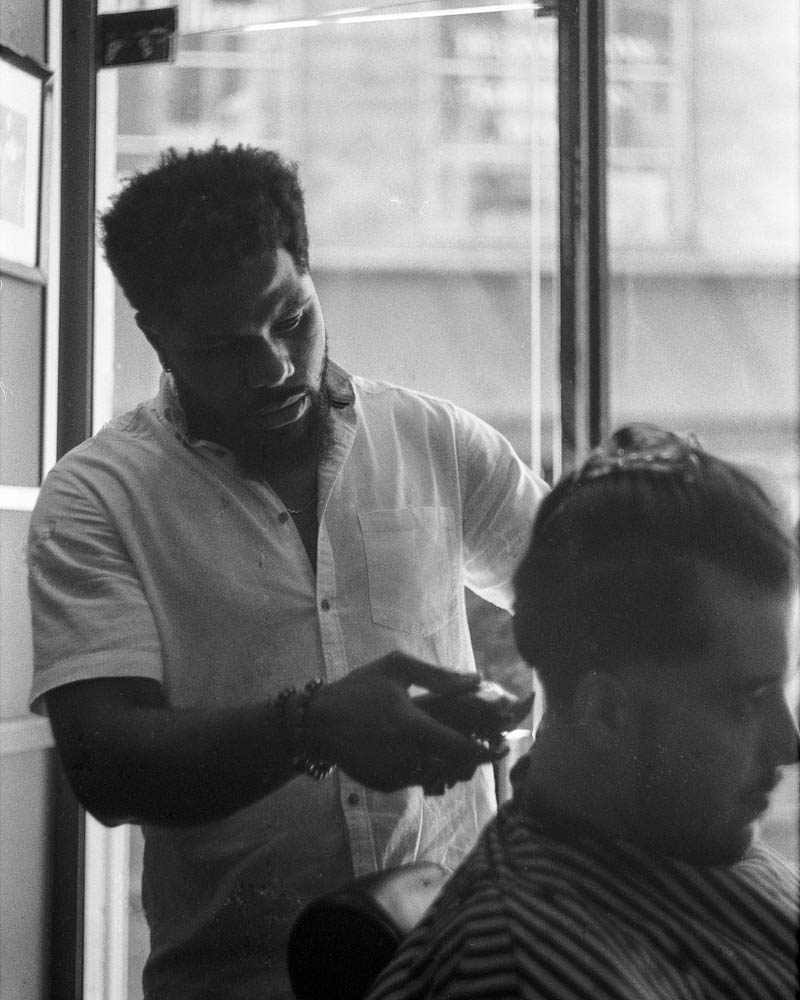

There was a time during the digital age when people sought to recapture the film aesthetic, and right on cue, apps like Hipstamatic, Instagram, and VSCO began to emerge. These digital tools embraced the nostalgic look of film, offering a nod to the past while thriving in the digital present. Yet, this digital simulation can’t quite match the authentic experience and emotional resonance of using actual vintage cameras.

This led me to a thought: if I truly wanted to capture that film aesthetic, why not use actual film and cameras from the eras I admire? I have always been drawn to “old” things, having loved exploring a special drawer at my grandmother’s house filled with genuine relics—not just my grandparents’ old possessions. My fascination with older technology, particularly when it’s still functional, remains strong. There’s an undeniable charm and satisfaction in using equipment that carries a legacy, offering a perspective that both honours the past and enriches the present.

So just because something might be old, it might still work and open a whole new world to you that you didn’t even suspect existed! It might, however, have something of a quirky nature, but once you get over that, the world is your oyster.