When I first started out in photography, I would go and get my film developed by the photographer on Newland Avenue near where I lived, and the photographer would do what people called a contact sheet. Basically, the film was cut into strips, placed into a special frame to keep the negatives as flat as possible, and exposed directly onto a sheet of photographic paper. These “thumbnails” allowed us to see the photos of the outing in one place and we could decide which ones might be worthy of developing.

We have this digital contact sheet in Lightroom where we import our photos and decide which ones are worthy of being developed. It’s the same idea, just with different tools.

But what does this have to do with storytelling? Think of the contact sheet as the beginning of the story-crafting process. Just like a narrative needs a beginning, middle, and end, so too does our selection of images. With a contact sheet, we gain a bird’s-eye view of an outing—seeing not only the individual shots but how they relate to each other. Choosing which moments to develop isn’t just about technical quality; it’s about deciding which parts of the experience best tell the story.

This principle guides me when choosing photos to share here on the blog. Whether it’s capturing moments with my friend JD, the barber, or snapping a shot of my lunch before I dive in, each image plays a role in the day’s story, hoping that I don’t forget to take the photo of my dessert before eating it. Otherwise you just get a photo of the plate with some traces of cake or just some crumbs.

But lets’s get back to the idea of story telling with an arc that covers the outing. When I set out for the day, I begin with a few warm-up shots to set the scene. If I have a plan, great—but often I don’t. Instead, I focus on capturing the ambiance of my surroundings, whether it’s a café, church, or pub. Each photo builds on the last, creating a narrative of my day’s journey.

For events, especially when I’m hired to photograph, I’ll start by discussing the plan with my client. I want to know what’s important to capture, any specific conditions at the venue—lighting, mobility restrictions, etc.—and what moments they consider essential. Having this list of must-capture moments, like the classic Kodak moments that we talked about in the last article, helps me stay focused and give me structure.

For the sake of arguments, I have a wedding to photograph, and I know that I will be taking shots of the bride before the ceremony. I know that I have to be at the venue before the happy couple arrives. I’d better get a shot of the rings before they appear on the couples’ fingers, etc. I’ll want environmental portraits of the guests, etc. This planning ahead allows me to be more serene during the day itself.

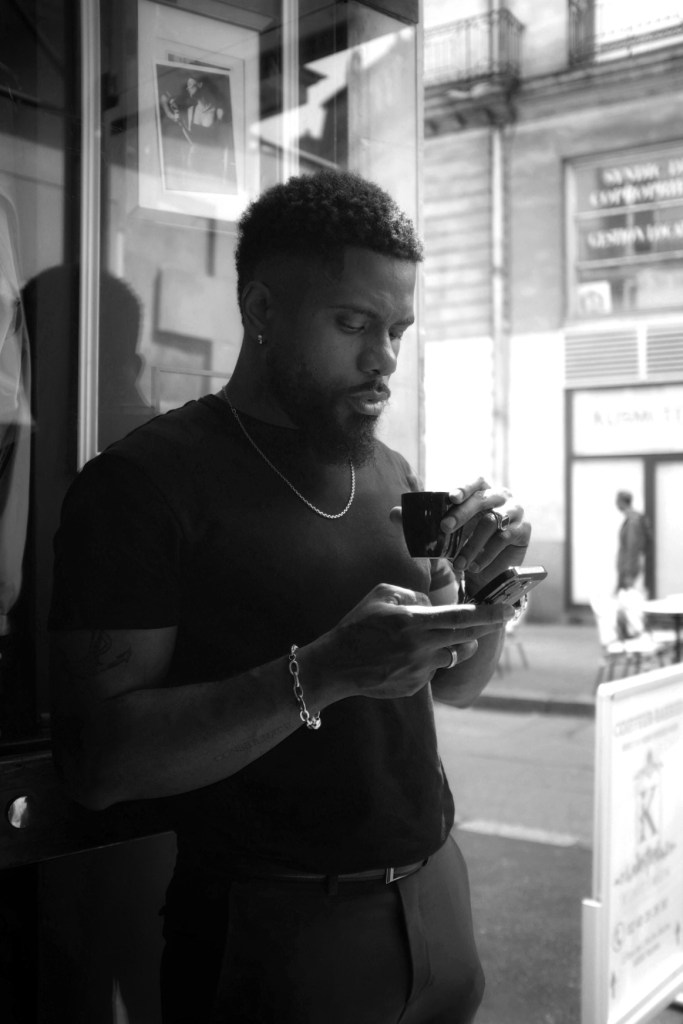

Not every story requires a series of images; sometimes, a single photograph can capture an entire narrative. Think of it as a self-contained story, a moment that holds not only what’s visible but also what’s implied—emotion, context, and sometimes, a sense of mystery.

For example, take a photograph of a lone, empty café table in the soft morning light, a half-full cup of coffee, and an open notebook on the table. This image can suggest solitude, introspection, or perhaps the moment right after someone has left. The viewer might wonder: Who was sitting here? Why did they leave? What were they writing? This photograph tells a story, inviting the viewer to step in and imagine the rest.

A single image can evoke different responses based on the viewer’s own experiences and emotions. In many ways, it’s a conversation between the photographer and the viewer. We as photographers might set the scene, choose the light, and capture the moment, but it’s the viewer who fills in the blanks, completing the story in their mind.

This approach also applies when photographing people. A portrait of a person lost in thought, gazing out of a window, can evoke curiosity about what’s on their mind, where they might be going, or what they’re experiencing at that moment. In these cases, the single image captures more than just a face or place; it holds an emotional narrative that transcends words.

Storytelling in photography isn’t just about taking pictures; it’s about deciding which moments matter and capturing them in a way that communicates more than what’s on the surface. Whether we’re crafting a narrative through a series of images or capturing an entire story in a single frame, each photo we take says something about how we see the world and what we want to share with others.

Next time you’re out with your camera, think about the story you’re building, whether it’s a quiet day at a café or a bustling event. What do you want your viewers to see, to feel, to wonder about? In some ways, we’re all storytellers—stringing together moments, big or small, to create something meaningful.

So, go on—look through your images as if they were frames in a film, each one a piece of a larger story. You might find that your perspective shifts, and that’s when photography becomes more than just a hobby; it becomes a way of understanding and connecting with the world.